Working From Home Was Supposed to Be the Big Revolution. The numbers tell a different story

The hybrid work dream and who gets to live it

Last week, during one of our team lunches- something we try to do on office days- a younger colleague looked up and asked, “Pre-pandemic, did you really go into the office every single day?”. A millennial colleague who also remembers the old routine and I exchanged a look, momentarily caught off guard. For many of them, the idea of commuting five days a week, spending money on transport and lunches every day, is almost unimaginable. Honestly, good for them!

It got me thinking about how much has changed – or perhaps, how much hasn’t. When the pandemic hit, headlines were full of bold predictions about the future of work (some linked below). Working from home was hailed as a revolution- offices would shut, workers would to larger homes in the suburbs, and digital nomads would take their laptops to beaches and mountaintops.

If you’re a hybrid worker, surrounded by people who split their time between home and office, it might feel like this way of working is the norm (I definitely do sometimes). You might be juggling the familiar challenges of staying motivated at home, disconnecting after work hours, or making the most of your office days. Or, if you’re a manager, you might be more concerned about maintaining team cohesion, protecting workplace culture, or ensuring fairness for employees with different levels of flexibility.

These are all important topics, but when you take a step back, the bigger picture reveals something more complex. There’s a deeper issue that often gets overlooked: inequality.

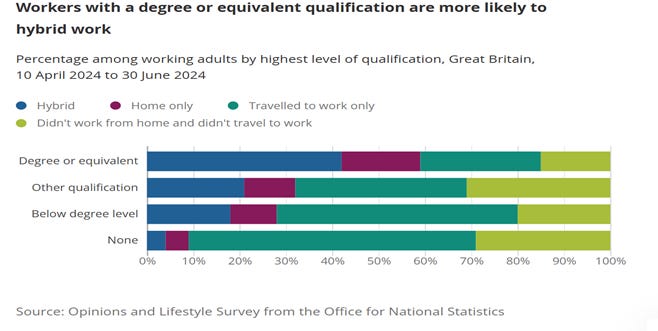

Data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) reveals a stark divide in who actually benefits from hybrid working arrangements. Far from being a universal revolution, hybrid working has become a privilege enjoyed by a select few.

Who Really Gets to Work Hybrid?

The ONS data shows that approximately a quarter of workers now have hybrid work arrangements. Unsurprisingly, hybrid work is more common among older workers (those over 30), parents, managers, professionals, and those in industries requiring minimal face-to-face contact. Workers with higher qualifications are also significantly more likely to work hybrid.

The disparity is stark. According to the findings, workers with a degree or equivalent qualification are 10 times more likely to work hybrid than those with no qualifications (42% compared with just 4%).

This divide suggests that access to hybrid work is closely tied to the type of jobs people do. Those with higher qualifications often have roles that can be performed remotely, such as professional or managerial positions. Meanwhile, those with lower qualifications are more likely to work in sectors like hospitality and retail, which require their physical presence.

The picture is similar in the United States. McKinsey research highlights how higher-income workers, particularly in technology and finance, are far more likely to work remotely. Meanwhile, lower-wage service workers are expected to show up in person. An urban-rural divide is also emerging, with remote work concentrated in cities that host high-paying knowledge economy jobs.

The divide also exists within organisations. Office-based staff often enjoy greater access to flexible arrangements, while frontline workers—such as retail staff, delivery drivers, and healthcare professionals—are left out.

A Workforce Divided

This growing inequality has created (at least) two distinct groups in the workforce:

Hybrid-eligible workers: Professionals with higher qualifications who enjoy flexibility, save commuting time, and can better balance work with personal well-being.

In-person workers: Predominantly those in lower-paid, lower-skilled roles, as well as some highly skilled but location-bound professions like healthcare, who endure longer commutes and limited flexibility.

The benefits of hybrid working are well-documented: better mental health, improved work-life balance, and increased productivity. However, those who are already disadvantaged in the labour market - young people, people from ethnically minoritised backgrounds, and those with disabilities - are more likely to work in low-paid and precarious sectors. These inequalities in working conditions accumulate over time, making it even harder to transition into higher-paying, more flexible roles.

I’m aware that big companies like Amazon and Citigroup and HSBC, which often employ high-paid professionals, have called workers back to the office, citing concerns over productivity, collaboration, and workplace culture. However, the core issue isn’t just where people work—it’s the control and autonomy they have over their working conditions. While some of these people might need to be back in the office, they can still enjoy flexibility in other aspects or have greater employment perks that would make up for the lack of hybrid working.

What Needs to Change

Research consistently shows that factors such as having control over how you work is critical in determining whether people stay in the workforce or leave. Hybrid working is just one facet of flexibility.

Organisations and advocates, including Timewise and disability groups, have long championed broader approaches, such as shift-swapping, part-time roles, or compressed hours—solutions designed to accommodate workers in roles that cannot be performed remotely.

For example, Timewise, partnered with the Institute for Employment Studies (IES), to explore flexibility in “hard-to-flex” sectors. Over two-years, they piloted changes in the three organisations with significant frontline roles, demonstrated the tangible benefits of flexible work. Results showed that:

Retention improved as workers found it easier to balance their responsibilities.

Sickness absence decreased, reflecting better well-being and reduced burnout.

Employee performance increased, as workers felt more empowered and engaged.

These findings underscore the untapped potential of flexible work arrangements across all sectors—not just those suited to remote work.

Policymakers are beginning to acknowledge these needs. In the UK, the Employment Relations (Flexible Working) Act 2023 made the right to request flexible working available from day one of employment. Labour’s Employment Bill promises to go further, but the proposals so far stop short of granting a universal day-one right. Instead, flexible working remains a “right to request,” leaving too much discretion to employers.

What’s needed now is bold legislation that establishes flexible work as the default, with exemptions only for roles where it is genuinely unfeasible. Employers, too, must rethink job design to incorporate flexibility into even the most traditional roles, ensuring no worker is left behind.

The Promise of a Revolution

The pandemic opened the door to a new way of working for some of us, but we’ve yet to walk through it fully—or allow others to join. In a world where we discuss the four-day work week and other modern labour reforms, we must ensure these changes benefit society as a whole, not just a privileged few.

Without deliberate action, the promise of a working revolution will remain unfulfilled, leaving countless workers bound to outdated systems. It’s time to make flexibility - whether it’s hybrid working, shift-swapping, or other solutions—must become a right, not a luxury.